Definition/Valuation

What is a Carbon Credit?

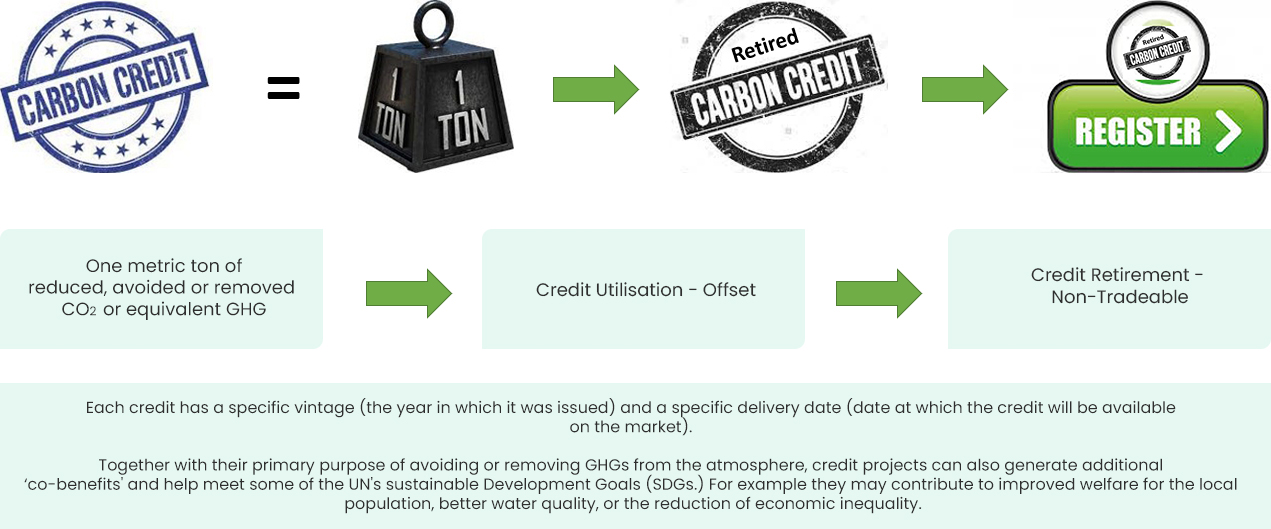

A carbon credit is a tradeable certificate that represents one metric ton of carbon dioxide (CO₂ ) or the CO₂ equivalent of another greenhouse gas that is prevented from entering, or removed from the atmosphere.

Carbon credits are important and in many cases essential tools on the path to achieving net zero, particularly for emissions that are difficult or impossible to reduce or abate.

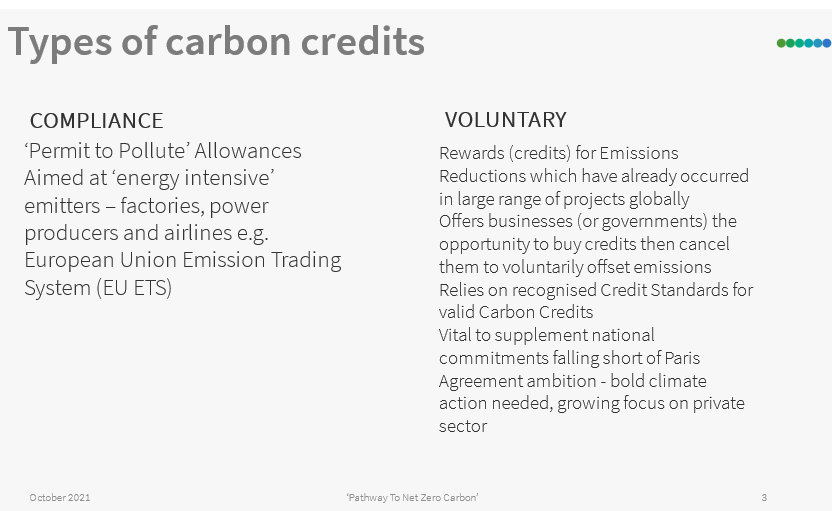

Compliant Carbon Credits

Voluntary Carbon Credits

The implementation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement on Nov 13 at the UN Climate Conference, or COP26, in Glasgow set the rules for a crediting mechanism to be used by the 193 parties to the Paris deal to reach their emission reduction targets or nationally determined contributions. The article implementation has made it possible for countries to buy voluntary carbon credits, as long as Article 6 rules are respected.

The surge in demand in Australia’s voluntary carbon markets is accelerating as companies act on decarbonisation commitments, with a record number of credits surrendered last quarter, according to the Clean Energy Regulator.

The total number of carbon credits and certificates surrendered – thereby contributing to emission reduction pledges – was up by 24 per cent year-on-year by the end of September to 2.7 million, the regulator said in its quarterly carbon market report.

By far the majority of the total were international carbon credits, which can be bought for a fraction of the price of higher-quality, domestically sourced Australian Carbon Credit Units. Large-scale renewable energy certificates are also included in the total, which could reach about one million this year, said Mark Williamson, executive general manager at the regulator.*131

"A Vibrant Carbon Market for a Low Carbon Future" – Opening Remarks by Mr Ravi Menon, Managing Director, Monetary Authority of Singapore, at the Climate Impact X Announcement Event on 20 May 2021

There is great opportunity to scale the voluntary carbon markets. Globally, the demand for voluntary carbon credits is expected to grow 15-fold over the next 10 years, to 2 billion tonnes in 2030.

More governments and companies are committing to net-zero targets.

Last year, 1,500 companies across the world made net-zero commitments, a three-fold increase from the year before.*117

I believe there are five key factors that determine the quality and hence the price premium achievable from a carbon credit unit.

- Firstly, the scheme it’s registered under. Some regulators are simply stricter than others, setting higher benchmarks for verification and reporting.

- Second, the location of the project generating carbon credit units. Proximity to the place of emissions is favoured by those seeking carbon-credit offsets. Building a story for co-locating credits and emissions is seen as beneficial to the surrounding communities.

- Third, project type. Nature-based solutions of creating carbon credits – for example, human-induced regeneration – supply most of Australia’s credits as they are the most cost-efficient to produce. Biodiverse tree-planting projects are now more expensive but may be the next major source of credits under higher carbon prices.

- Further, many of the methods that capture and remove carbon rather than just avoid producing it are more attractive to buyers. Any additional co-benefits given to the land or the community from the project are the fourth beacon of quality.

- Finally, the age of the project (or its vintage) is important. Buyers want to demonstrate their carbon credit purchase is benefiting the land now. It is less advantageous to spend money on a project that was done five years ago.*118

As addressing climate change has become an increasingly urgent political priority, policy makers have been keen to develop the available tool kit to address this challenge. Within that tool kit, carbon pricing plays an important role as it has been identified as one of the most effective ways of reducing greenhouse gas emission levels on the domestic and international level. In some markets, carbon prices have been rising rapidly over the recent past and are forecast to do so for years to come. The commodities markets across the value chain will need to prepare for and adapt to these new prices.*119

Big companies, such as Microsoft Corp. and BP PLC, are on the hunt for offsets as well – to show investors their commitment towards achieving climate change goals.

Though many companies are developing technology to reduce their emissions or even capture and store their emissions, carbon credits are an effective and immediate way to offset carbon, improve the environment, and even stimulate economic development, which is why interest is at an all-time high.

Governments and companies alike are working fervently to meet regulations set by the Paris Agreement, and carbon offsets have a significant role to play.*120

The incredible boom in demand for investments with a focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors was another tailwind for private wealth firms specialising in this nascent market, estimated by Morningstar to be worth US$1.7 trillion ($2.3 trillion) and growing.

“The biggest demand we see is an increase in social purpose in investing, whether you call it ESG or impact investing,” Mr Heath, a former chief of National Australia Bank’s JBWere private wealth arm said, projecting that the niche would become even more lucrative as wealth was transferred from Baby Boomers to Generation X and Millennial beneficiaries over the next three decades.*121

Australian fund manager Tribeca Investment Partners is trying to stay ahead of the pack, signing a new carbon credits investment joint venture and raising a new fund.

The new joint venture will start life with about $500 million of credits, picked up through a combination of secondary market purchases and primary offtake agreements with developers.

VT Carbon is trying to get ahead of the competition, jumping in when carbon credit markets are in their infancy and trading infrastructure is relatively immature.

For financial investors, the fund is a punt on increasing demand for carbon credits, which would suggest rising prices.*122

Carbon pricing programs typically take the form of taxes on polluters’ emissions or “cap and trade” systems that limit how much companies can emit before having to pay more.

The World Bank outlines 64 such initiatives in 45 countries, although they cover less than 22 per cent of global emissions and most use carbon prices that are too low to incentivise heavy emitters to change their business models.

The EU, meanwhile, has taken a more aggressive approach. It is extending its own carbon pricing scheme to new sectors within the bloc and has promised to impose a carbon border tax on imported goods.*123

Get in Touch

Sign up to our regular newsletter

"*" indicates required fields